My Grandson, Climate Change, Drought and that Children’s Book

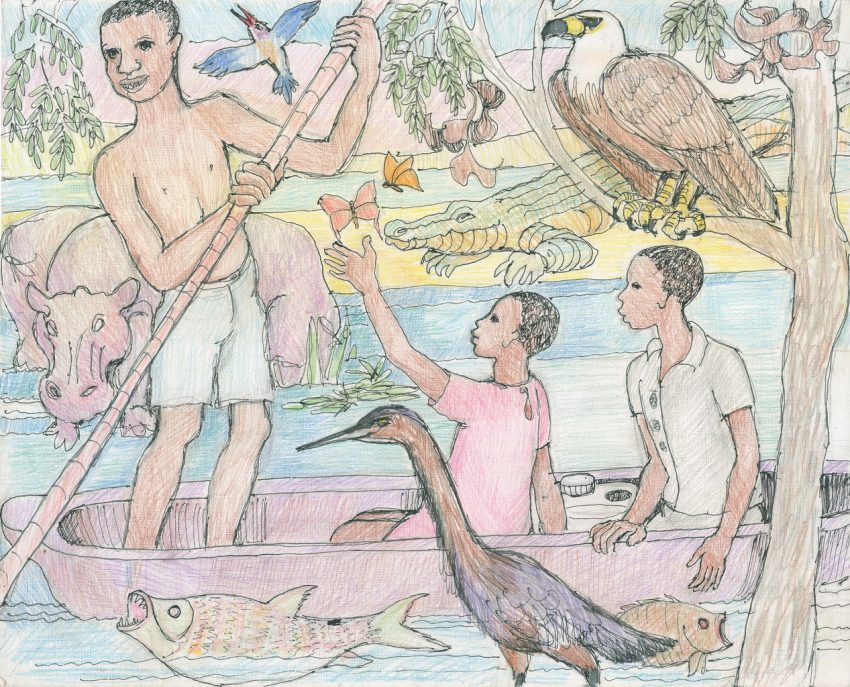

On the Zambezi River

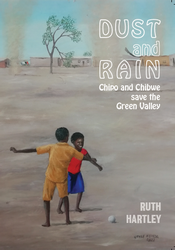

In 1993, while sitting in a boat on the Zambezi River floodplain, far north of Mongu, watching the beautiful flights of hundreds of pelicans, I began to make notes and sketches for a book about climate change for my grandson, Stephen Kupakwesu Bush. It was called The Drought Witch. Stephen was 3 years old. It would not be until 2022, after years of hard work editing and adapting it, that the book was published in Zambia by Gadsden Publishers as Dust and Rain: Chipo and Chibwe save the Green Valley. A lifetime later, Stephen is 35 and a successful political journalist at the Financial Times in London. My life has also changed, but my passions for gardening, human rights, art, and my concerns about climate change, Africa and my children and grandchildren have not.

Climate Change: a Recognised Reality for over 50 years

Climate change was a serious concern for me long before 1990. My first book, The Shaping of Water, focuses on the environmental impact of the Kariba Dam. Climate change is not a one-off cause that I selected to write about in this kids’ book. I grew up on farms with my stepfather and father, watching the skies for the first rains to break the drought of the dry season. In 1992, my first husband, Dr Mike Bush, and I attended a medical conference in Canada where a seminar was given by Helen Caldicott, MD, an Australian, whose book If You Love This Planet is about climate change.I knew Silent Spring (1962) by Rachel Carson, and since 1970, I haven’t used pesticides on plants in any of my gardens. I took my daughter, Tanvir, to a permaculture workshop in Zimbabwe in the 1980s and made a permaculture garden in Zambia. Today, I’m watching the heat of a changing climate kill the plants in my garden.

A Bad Woman from a Wicked Past is a Bad Mother

I wrote my memoir, When I Was Bad, primarily for my oldest daughter, but it is for all my kids. When a parent has a disrupted and uprooted life, it is common for the children not to know or understand why things happened the way they did. Secrets and lies can be indistinguishable from each other until the truth and facts are made plain. Divorce, racial politics, the end of colonialism and the liberation wars ruptured my chances of a secure life, so the choices I was forced to make were radical and challenging. Some of these issues are in my short story and memoir book, When We Were Wicked, which is about that past. My family is of mixed heritage, both African and European. It is also multi-ethnic and includes Jews, Muslims, Christians and agnostics. When I started my London life as a single mother in 1966, women were not equal to men under the law, Blacks were not equal to Whites, and there were no guidebooks to life in the future. Few choices are simple to make, and often all that anyone can do is ride the storm waves and try not to drown. We are all subject to unforeseeable and life-changing accidents. How can a parent keep their family safe by ignoring the social, political and environmental problems everyone faces? I’m an ordinary, fearful woman who did her best, but of course, I made mistakes. I wanted to make a good home for my children, but I believed that we had to care for the equality of all people and the planet’s environment at the same time.

The Drought Witch transforms into Dust and Rain

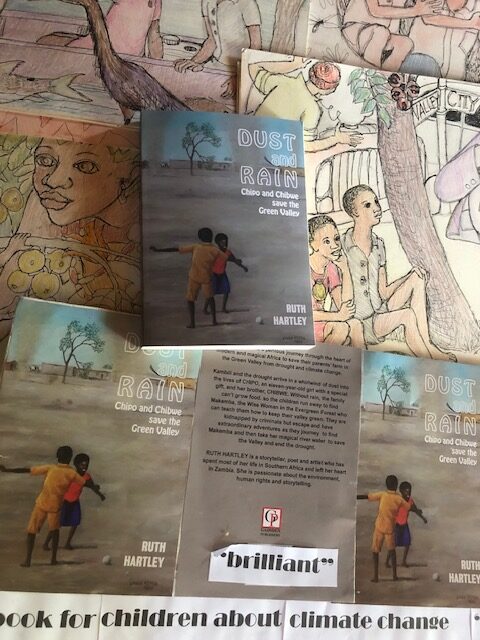

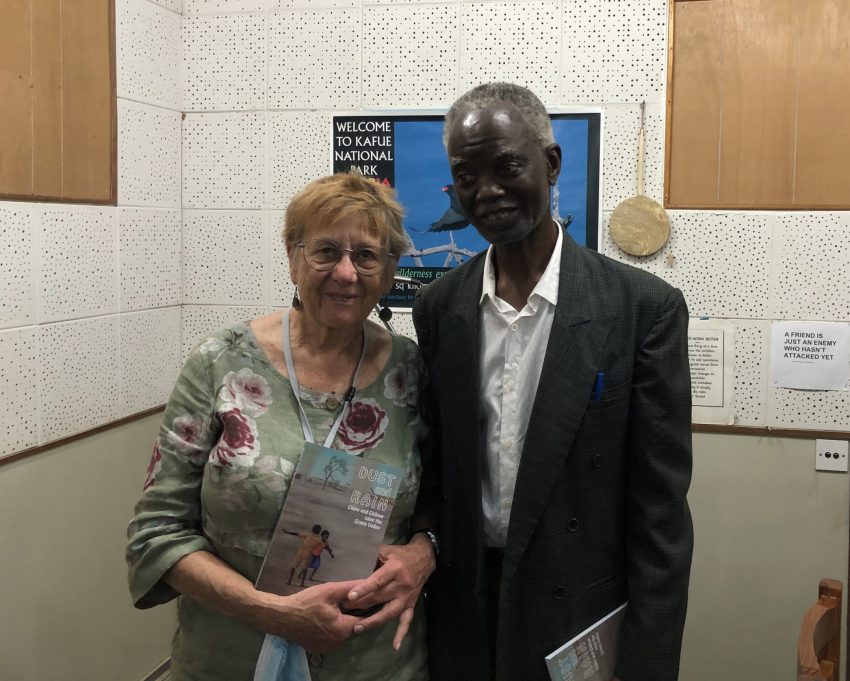

That story is yet another story of how the world changes in ways we can’t control. At St Martin’s Art School in 1995, I learned how to make a children’s picture book, but publishers didn’t think there was a market for a book about African children and climate change then. I wrote sequels to the book. I rewrote the stories as a longer novel and then as a series. The story was rejected for publication in Zimbabwe by women who wanted all the names to be Zimbabwean, a complicated matter to do with meanings, I think. The main character in the original book was named Kupakwesu after my grandson, but as time passed, I wanted his sister to be his equal and a hero too, so the names went through many changes. Finally, I paid for some marketing and literary advice from Cornerstones Literary Consultancy and then sent the story to Fay Gadsden in Zambia. The story was scrutinised for ethnic accuracy, choice of names, as well as quality of writing, until at last it was published as Dust and Rain: Chipo and Chibwe save the Green Valley. I am very grateful to Fay indeed, and I was delighted to go to Zambia to promote the book, as I’ve recorded in several blog posts.

Books, Readers, Sales and Help Promoting Dust and Rain

The main difficulty with my book is its cost for a Zambian child. It is a widespread problem in Africa. There are good writers and enthusiastic readers in Africa, but the cost of a book is still too high in relative terms. There aren’t enough libraries or enough books in them. This subject is currently being researched by my husband, Dr John Corley for his MA dissertation on literature. Environmental and wildlife clubs and agencies want the books, but they need donations to cover the costs. I will forgo my royalties. Please help in any way you can. Buy Dust and Rain. Read the book. Recommend the book. Review the book. Donate the book. Take a journey down the incredible and beautiful Zambezi River with Chipo and Chibwe and help them save the Green Valley and the world from drought and climate change.